Update (24/05)

This text has been revised and edited by ChatGPT 3.5 to improve grammar and overall structure.

Update (25/05)

Some links that I recommend, that are likely better than what I’ve written here:

- Chapter 1: Transformers of Jacob Hinton’s deep learning curriculum. Also, all the links inside it. I strongly recommend doing the exercise, which is exactly what I’ve done below.

- Transformer Circuits by Anthropic, in particular the “Transformer Overview” section.

- GPT-3 Paper and InstructGPT Paper.

Preamble

While delving deeper into the study of language models, I am currently following the curriculum developed by Jacob Hilton, which can be found at this GitHub repository. The initial exercise within this curriculum involves building a language model from scratch and training it on the works of Shakespeare.

What is this tutorial?

This is the first part of a tutorial on language models, specifically focusing on GPT models. It is a relatively concise tutorial that assumes the reader has some background knowledge in deep learning, and I make use of mathematical notation throughout.

This part guides us on the journey from nothing to “pure” GPT models, which serve as the foundation for language models like ChatGPT (those are also called base models or foundation models). In the next part, we will delve into the transition from “pure” models to fine-tuned models such as ChatGPT. This tutorial provides operational instructions, explaining how we arrive at specific language models. The reasons behind their functioning will be explored in a future post.

My primary motivation here is to learn through writing, while also addressing the lack of comprehensive transformer tutorials. It is quite astonishing that there are so few well-crafted tutorials or explanations for what is arguably the most significant revolution in deep learning in the past decade. This tutorial is another, albeit opinionated, attempt to fill that gap and may prove useful to some.

Now, you might wonder why you should care. I might provide an introduction later, but to be honest, simply experimenting with ChatGPT for a while should be enough to motivate your interest in language models.

Language models - evaluation.

Operationally, a language model can be thought as following the rule “given string \(s\) of natural language, output string \(w\) with probability \(p(w\mid s)\). This is what GPT-like models do at the end of the day. So the question is how to do that? For instance, when writing \(s = \text{``I ate a ''}\), the model outputs \(w = \text{``banana at the market''}\) with probability \(p(w\mid s) = 0.8\), as an example. The point is how the model does that?

First, we need to map \(s\) and \(w\) into some suitable structure for our model. We do this by making use of a “sequencing function” \(T\) that will map strings \(s\) to finite sequences of integers \(\mathbf{x} = (x_1, \ldots, x_n)\), with elements belonging to a finite set \([n_{vocab}] = \{1, \ldots, n_{vocab}\}\) which we call the vocabulary, \(n_{vocab}\) being the vocabulary size, that is, the “words” that the sequence model knows. We reserve \(1\) for the “end-of-sentence” token, that will be explained below. As an example, we transform the sequence \(s = \text{``I ate a''}\) into a sequence \(\mathbf{x} = (10, 123, 2)\).

Now, we transformed our language evaluation problem into an equivalent sequence evaluation problem, as follows: let \(\mathbf{x} = (x_1, \ldots, x_n)\) be a sequence in our vocabulary \([n_{vocab}]\). Our sequence model will output another finite sequence \(\mathbf{y}=(y_1, \ldots, y_m)\) with probability \(p(\mathbf{y}\mid \mathbf{x})\). Now, we can turn this sampling problem into a next-item prediction as follows: consider \(\mathbf{y}\) be a \(m\)-sized sequence as above, and consider \(1\) to signal the end of a sequence. Then, starting with \(\mathbf{y} = ()\), we will, repeatedly,

- Sample \(y_{i+1}\) from \(p_M(y\mid x_{1},\ldots, x_n, y_1, \ldots, y_i)\). If \(y_{i+1} = 1\) stop, and return \(\mathbf{y} = (y_1, \ldots, y_i)\).

- Update \(\mathbf{y}\) to \(\mathbf{y} = (y_1, \ldots, y_i, y_{i+1})\).

That is, we use the chain rule of probability to sample \(\mathbf{y}\) with probability letting \(\mathbf{y}^i = (y_1, \ldots, y_i)\), and letting \(\mathbf{x}\mathbf{y}\) be the concatenation of two sequences, we find that

\[p(\mathbf{y}\mid \mathbf{x}) = p_M(1\mid \mathbf{x}\mathbf{y})\prod_{i=1}^{n-1} p_M(y_{i+1}\mid \ \mathbf{x}\mathbf{y}^i),\]with \(\mathbf{y}^i := (y_1, \ldots, y_i)\), and \(\mathbf{x}\mathbf{y}\) denoting the concatenation of two sequences \(\mathbf{x}\) and \(\mathbf{y}\). Therefore, our model \(M\) will only output a single number \(y \in [n_{vocab}]\), given a sequence \(\mathbf{x} = (x_1, \ldots, x_n)\) also in \([n_{vocab}]\), with probability \(p_M(y\mid \mathbf{x})\). The chain rule will take care of the rest, and such a model will be called an autoregressive model.

Finally, given the sequence \(\mathbf{y}\), we can unsequence it to get string \(w\). We do that by applying an inverse sequencing function \(T^{-1}\) to each element of \(\mathbf{y}\), getting a string \(w = T^{-1}(\mathbf{y})\). Thus, our language model consists of a sequence model \(M\) predicting the next token, and a sequencing/unsequencing pair \((T, T^{-1})\). We have \(p_{M, T}(w\mid s) = p_M(T(w)\mid T(s))\), and we sample \(w\) by sequencing \(s\) into \(\mathbf{x}\), sampling \(\mathbf{y}\) from \(M\) given \(\mathbf{x}\), and unsequencing \(\mathbf{x}\) into \(w\).

An example of how this works is transforming \(s = \text{"I ate a"}\) into \(\mathbf{x} = (10, 123, 2)\), sampling \(12 \sim p_M(y\mid 10, 123, 2)\), \(4 \sim p_M(y\mid 10, 123, 3, 12)\), \(7 \sim p_M(y\mid 10, 123, 3, 2, 4)\), \(71 \sim p_M(10, 123, 3, 2, 4, 7)\), \(1 \sim p_M(10, 123, 3, 2, 4, 7, 71)\), and unsequencing \(\mathbf{y} = (12, 4, 7, 71)\) into \(w = \text{"banana at the market"}\). Next, we show how this works in a code.

#Write an autocomplete function and evaluate on a model

#trained on the complete works of Shakespeare.

def autocomplete(model, string, maxiter=128):

#The next line is responsible for the sequencing

base = torch.tensor(vocab(tokenizer(string))).to(DEVICE)

nmax = model.nctx #We guarantee our model not surpasses context window

for _ in range(maxiter):

out = model(base[-nmax:])[-1, :] #Output the log-probabilities

ind = torch.multinomial(torch.exp(out), 1) #Sample from output

base = torch.cat([base, ind], axis=-1) #Append to our sequence

if ind.item() == 0: #Here we are using 0 instead of 1 for end-of-senence

break

#The next line is responsible for the desequencing

output = detokenizing(vocab.lookup_tokens(base.cpu().tolist()))

return output

print(autocomplete(model, 'QUEEN OF WALES'))

"""

QUEEN OF WALES

RICHARD, and KEEPER at Bordeaux.

I have leisure kept together,

Which of twelve thousand looks in France,

Against the French Duke of Norfolk,

Whose power of Hereford, Donalbain, speed,

Under your progenitors, charming arms, Edward’s blood,

And care not his father lives at MALCOLM.

It may not be discharged truth,

Where let, Harry to prevent enacted ships

To pay, and princes if can be bold

But must suspect ere we bid be alive

To follow them to the King with passage.

My noble lord, prince. I have sounded London,

So many the living time

"""

Sequencing, tokenizing and indexing.

Now, the task of transforming a string into a sequence of integers, which we will call identifiers or ids, consists of two parts:

- Splitting the string into words and subwords, which we refer to as tokens, using a tokenization rule. For example, transforming “I love you” into (“I”, “love”, “you”).

- Using a lookup table to transform a sequence of tokens into a sequence of identifiers by assigning a unique identifier to each token in our vocabulary, which is our list of known tokens.

The second part is relatively straightforward. We associate each token in our vocabulary with a unique identifier and use this lookup table to convert our sequence of tokens into a sequence of identifiers. In cases where a token is not found in our vocabulary, we can assign it a special unknown identifier.

The first part, tokenization, is more complex, and various tokenization algorithms exist. A comprehensive tutorial can be found here. However, for now, let’s assume that each word and each sentence is treated as a token (which is a valid tokenization approach). When mapping a sequence back, we can simply invert our lookup table, associating the “unknown” identifier with a blank sentence or a <unk> symbol, and concatenate our tokens according to a specific rule (such as the regular grammar rule for joining words and punctuation). Below, we provide an example of tokenization using spaCy.

#Here, we create a vocabulary from the works of Shakespeare,

#and use the Spacy tokenizer.

site = "https://www.gutenberg.org/files/100/100-0.txt"

data_string = urllib.request.urlopen(site).read().decode('utf-8')

#Tokenizer our data using Spacy tokenizer, to create a vocabulary

tokenizer = torchtext.data.utils.get_tokenizer('spacy')

tokens = tokenizer(data_string)

#Create a vocabulary from tokens

sorted_tokens_freq = collections.OrderedDict(

sorted(collections.Counter(tokens).items(), key = lambda x : x[1], reverse=True)

)

vocab = torchtext.vocab.vocab(sorted_tokens_freq, specials=['<unk>'])

vocab.set_default_index(vocab['<unk>'])

#Create a detokenizing function

def detokenizing(tokens):

words = [(' ' + s if s.isalpha() else s) for s in tokens]

return ''.join(words)

print(tokenizer("hello my friend"))

#--> ['hello', 'my', 'friend']

print(vocab(tokenizer("hello my friend")))

#--> [0, 15, 292]

print(vocab.lookup_tokens([5, 20, 10]))

#--> ['the', 'is', 'of']

print(detokenizing(vocab.lookup_tokens([5, 20, 10])))

#--> the is of

Training the sequence model.

Now, our goal is to have our model \(M\) as a function that, for a given evaluation sequence \(\mathbf{x}^{eval} = (x_1^{eval}, \ldots, x_{n_{eval}}^{eval})\), outputs \(p(y\mid \mathbf{x}^{eval})\) for each \(y = 1, 2, \ldots, n_{vocab}\). This allows us to sample \(y_{n_{eval}}^{eval} \sim p(y\mid \mathbf{x}^{eval})\). To achieve this through supervised learning, we need training pairs \((\mathbf{x}^{train}, y^{train})\) to train our model. Let’s consider a single sentence \(\mathbf{x} = (x_1, \ldots, x_n)\) as our training data. From this, we can infer that \((x_1)\) should output \((x_2)\), \((x_1, x_2)\) should output \(x_3\), and so on. Therefore, we end up with \(n-1\) training pairs of the form \((\mathbf{x}^i, x_{i+1})\) for \(i = 1, \ldots, n-1\). We will use this fact to design a neural network \(f_\theta\) that takes finite sequences \(\mathbf{x} = (x_1, \ldots, x_n)\) as input and outputs an \(n \times n_{vocab}\)-sized matrix \(f_\theta(\mathbf{x})\), where the elements are given by \(f_\theta(\mathbf{x})_{i, j} = p(j\mid \mathbf{x}^i)\).

Next, we need to define a loss function. For a given sequence \(\mathbf{x}\), we can use the negative log-likelihood to define our loss function \(l\) for parameters \(\theta\) as

\[l(\theta;\mathbf{x}) = -\sum_{i=1}^{n-1} \log p(x_{i}\mid \mathbf{x}^{i}) = -\sum_{i=1}^{n-1} \log f_\theta(\mathbf{x})_{i, x_{i}+1}\]To ensure that this approach works, we need to make sure that when passing \(\mathbf{x}\) to \(f_\theta\), the output \(f_\theta(\mathbf{x})_{i}\) only depends on \(\mathbf{x}^i\) and does not incorporate any information from subsequent tokens. In other words, it should not use any information from \(x_{i+1}\) itself or from “future” positions, as that would be considered “cheating.”

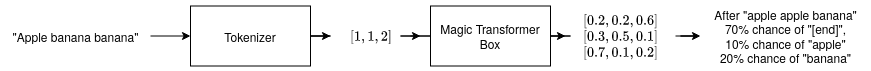

For now, let’s imagine \(f_\theta(\mathbf{x})\) as a “magic transformer box.” The schematics of our language model work as shown in the following figure, which predicts with 70% chance that the sentence ends after the phrase “apple banana banana”.

In the next steps, we will apply this “magic transformer box” philosophy to train the GPT model using the complete works of Shakespeare (actually, just 80% of them).

#Create our train and text dataloader.

def batchify(x, line_size=64):

tensor_size = x.shape[-1]

nbatches = tensor_size//line_size

overhead = line_size - tensor_size%line_size

if overhead != 0:

x = torch.nn.functional.pad(x, (0, overhead))

nbatches += 1

new_size = x.shape[:-1] + (nbatches, line_size)

x = x.reshape(*new_size)

return x

line_size=64

data_tensor = batchify(torch.tensor(vocab(tokens), dtype=torch.long), line_size)

dataset = torch.utils.data.TensorDataset(data_tensor.to(DEVICE))

train_dataset, test_dataset = torch.utils.data.random_split(dataset, [0.8, 0.2])

train_dataloader = torch.utils.data.DataLoader(train_dataset, batch_size=32, shuffle=True)

test_dataloader = torch.utils.data.DataLoader(test_dataset, batch_size=32, shuffle=True)

#Create our model

model = GPT(len(vocab), line_size-1, dembed=64, nlayers=6, nheads=8, dk=8, dv=8, nhidden=64)

model.to(DEVICE)

model.train()

lr = 1e-2

optimizer = torch.optim.Adam(model.parameters(), lr=lr)

scheduler1 = torch.optim.lr_scheduler.StepLR(optimizer, 1.0, gamma=0.95)

scheduler2 = torch.optim.lr_scheduler.CosineAnnealingWarmRestarts(optimizer, 10, eta_min=1e-5)

nepochs = 100

print_frequency = 100

min_loss = math.inf

#Train our model

for epoch in range(nepochs):

model.train()

for step, [x] in enumerate(train_dataloader):

optimizer.zero_grad()

loss = loss_fn(x, model)

loss.backward()

torch.nn.utils.clip_grad_norm_(model.parameters(), 1e-1)

optimizer.step()

if loss < min_loss:

min_loss = loss

best_model = copy.deepcopy(model)

scheduler1.step()

scheduler2.step()

print(f"Epoch : {epoch}, loss : {min_loss}")

Opening the “magic transformer box”.

In a sense, the following is optional. Many GPT models can be understood by considering transformers as black boxes and focusing on how they are trained. However, the model has a rich inner architecture, and it can be valuable to understand this architecture.

So, feel free to skip to the “Conclusion” section, but also feel free to continue reading.

Notation

From now on, we will be dealing with tensors of order higher than two, as this simplifies the notation for transformers. Hence, we will use the Einstein notation, where statements such as \(\mathbf{a}_{ij} \mathbf{b}_j\) are equivalent to \(\sum_j \mathbf{a}_{ij} \mathbf{b}_j\). We will refer to elements of a tensor using lowercase bold letters, such as \(\mathbf{a}\), and the entire tensor using uppercase letters, such as \(\mathbf{A}\). Moreover, we will use a specific notation to refer to column and row vectors of a matrix. For example, if \(\mathbf{A}\) is a matrix (a second-order tensor), \(\mathbf{a}_{i \circ}\) refers to the \(i\)-th row vector of \(\mathbf{A}\), and \(\mathbf{a}_{\circ j}\) refers to the \(j\)-th column vector of \(\mathbf{A}\). Similarly, if \(\mathbf{B}\) is a third-order tensor, \(\mathbf{b}_{\circ j k}\) refers to the vector obtained by selecting indices \(j\) and \(k\) in the second and third positions, and \(\mathbf{b}_{i \circ \circ}\) refers to the submatrix obtained by selecting \(i\) in the first position. Furthermore, we use \(\mathbf{W}\) (with superscripts) to denote learnable parameters of our layer. Finally, \(\mathbf{1}_{\text{condition}}\) refers to the function that has a value of 1 if the condition is satisfied, and 0 otherwise. For example, \(\mathbf{1}_{i = j}\) is a function of \(i\) and \(j\) that equals 1 if \(i = j\) and 0 otherwise.

Embedding

Embedding is the operation of transforming sequences into vectors using a learnable lookup table. Suppose we have \(n_{vocab}\) items in our vocabulary and we want to associate each token with a \(d\)-dimensional vector. We set up a learnable matrix \(\mathbf{W}^e\) of size \((n_{vocab}, d)\), and for a sequence \(\mathbf{x}\) of size \(n\), the embedding of \(\mathbf{x}\) is given by a matrix \(\mathbf{V}\) of size \((n, d)\), where the \(i\)-th row is given by \(\mathbf{v}_{i \circ} = \mathbf{w}^e_{x_i \circ}\).

Next, we need information about the position of token \(x_i\). In the original transformers paper, this is achieved using a fixed vector \(p_i\), where the \(j\)-th value \(p_{i, j}\) is equal to \(\sin \frac{i}{10000^{j/d}}\) if \(j\) is even, and \(\cos \frac{i}{10000^{(j-1)/d}}\) if \(j\) is odd. This is combined with the token embedding by adding the positional embeddings to the corresponding token embeddings, resulting in

\[\mathbf{v}_{i, \circ} = \mathbf{w}^e_{x_i \circ} + p_i.\]Alternatively, instead of using fixed positional embeddings, we can use learned positional embeddings for a context window of maximum size \(n_{ctx}\). In this case, we introduce a learnable matrix \(\mathbf{W}^{pos}\) of size \((n_{ctx}, d)\), and the positional embeddings are given by

\[\mathbf{v}_{i\circ} = \mathbf{w}^e_{x_i \circ} + \mathbf{w}^{pos}_{i \circ}.\]The total number of parameters here will be either \(d n_{vocab}\), if positional embeddings are fixed, or \(d n_{vocab} + d n_{ctx}\), if positional embeddings are learned.

Unembedding

The transformer operation, which will be explained in detail below, takes as input an embedding matrix \(\mathbf{V}\) of size \((n, d)\) and outputs another matrix \(\mathbf{V}'\) of the same size \((n, d)\). We need to associate each \(\mathbf{v}_{i \circ}\) with the probability \(p(x_{i+1}=u\mid \mathbf{x}^i)\) of the next token (at position \(i+1\)) having a value \(u \in [n_{vocab}]\). To achieve this, we:

- Employ a linear layer with a weight matrix \(\mathbf{W}^u\) of size \((d, n_{vocab})\) and a bias vector \(\mathbf{b}^u\) of size \((n_{vocab})\). This transformation is given by \(\mathbf{v}_{ij}' = \mathbf{v}_{ik} \mathbf{w}^u_{kj} + \mathbf{b}^u_j\).

- Apply the softmax function to each row of the resulting matrix, yielding an output matrix \(\mathbf{Y}\) of size \((n, n_{vocab})\), where \(\mathbf{y}_{iu} = p(x_{i+1} = u\mid \mathbf{x}^i)\).

The total number of parameters here will be \(d n_{vocab} + n_{vocab}\).

Attention

Now we can delve into the core of the transformer architecture. Let’s start by considering the real matrix \(\mathbf{V}\) of dimensions \((n, d)\) obtained from embedding the sequence \(\mathbf{x}\) in \(d\) dimensions. An attention layer performs the operation

\[\mathbf{v}_{ij} \to \mathbf{a}_{ik} \mathbf{v}_{kj},\]where \(\mathbf{A}\) is a matrix of dimensions \((n, n)\), such that \(\mathbf{a}_{ik} \geq 0\) and \(\sum_k \mathbf{a}_{ik} = 1\). In other words, the attention matrix \(\mathbf{A}\) computes the weighted mean \(\mathbf{a}_{ik} \mathbf{v}_{k \cdot}\) of the embedding vectors at other positions for each position \(i\).

The attention matrix \(\mathbf{A}\) is determined by two other matrices: the query matrix \(\mathbf{Q}\) and the key matrix \(\mathbf{C}\), both of dimensions \((n, d^q)\), where \(\mathbf{a}_{ik}\) informally measures the “similarity” between \(\mathbf{q}_{i\circ}\) and \(\mathbf{c}_{k\circ}\). In transformers, this similarity is defined by the “score function”

\[\operatorname{score}(\mathbf{q}_{i \circ}, \mathbf{c}_{k \circ}) := \left<\mathbf{q}_{i\cdot}, \mathbf{c}_{k\cdot}\right>/\sqrt{d^q}.\]The idea is to measure similarity using an inner product, normalized by \(\sqrt{d^q}\) for stability. The score function is then transformed by applying the softmax function to each row of the score matrix, yielding

\[\mathbf{a}_{ik} := \frac{e^{\operatorname{score}(\mathbf{q}_{i\circ}, \mathbf{c}_{k \circ})}}{\sum_k e^{\operatorname{score}(\mathbf{q}_{i\circ}, \mathbf{c}_{k \circ})}}.\]Therefore, the attention operation \(\operatorname{attn}\) is defined as

\[\mathbf{V}' = \operatorname{attn}(\mathbf{V}, \mathbf{Q}, \mathbf{C}),\]where \(\mathbf{V}'\) has dimensions \((n, d)\).

Now, what are the query matrix and the key matrix? In self-attention, the query matrix \(\mathbf{Q}\) and the key matrix \(\mathbf{K}\) are derived from \(\mathbf{V}\) itself using learnable linear operations on each row of \(\mathbf{V}\), which represents each embedding vector. Specifically, we have

\[\mathbf{q}_{ij} := \mathbf{v}_{il} \mathbf{w}^q_{lj},\]and

\[\mathbf{c}_{ij} := \mathbf{v}_{il} \mathbf{w}^c_{lj},\]where \(\mathbf{W}^q\) and \(\mathbf{W}^c\) are both matrices of dimensions \(d \times d^q\) (with \(d^q < d\) usually). Not only that, but we make the attention operation on a learnable projection of the embedding vectors of $\mathbf{v}_{ij}$ to a subspace of dimension $d^v$, using a matrix \(\mathbf{W}^v\) of dimensions \(d \times d^v\), such that we apply \(\mathbf{a}_{ik}\) to \(\mathbf{v}_{kl} \mathbf{w}^v_{lm}\). Of course, that results in a matrix of dimension $(n, d_v)$, so we must undo the projection using another learnable matrix \(\mathbf{W}^o\) of dimensions \(d^v \times d\) to return to dimension $(n, d)$. Consequently, the self-attention operation can be expressed as

\[\mathbf{v}_{ij} \to \mathbf{a}_{ik} \mathbf{v}_{il} \mathbf{w}^v_{lm} \mathbf{w}^o_{mj},\]where

\(\mathbf{a}_{ik} = \operatorname{softmax}_k \left[ \left<\mathbf{v}_{il} \mathbf{w}^q_{l\cdot}, \mathbf{v}_{kl} \mathbf{w}^c_{l\cdot} \right>/d' \right].\) As a side note, notice that \(\mathbf{w}^v_{lm} \mathbf{w}^o_{mj}\) can be thought of as a linear operator operating on the embedding dimension of \(v\), of low-rank with \(d_v < d\). We denote the operator as

\[\mathbf{V}’ = \operatorname{sattn}(\mathbf{V};\mathbf{W}^q, \mathbf{W}^c, \mathbf{W}^v, \mathbf{W}^o).\]Yet, there is an essential consideration missing here. We want the output corresponding to the \(i\)-th token to depend only on tokens \(k \leq i\). The previous formulation does not ensure this because in general, \(\mathbf{a}_{ik}\) can be greater than zero even if \(k > i\), meaning that the \(i\)-th position utilizes information from positions ahead. To address this, we need to introduce a mask in such cases to enforce \(\mathbf{a}_{ik} = 0\) if \(k > i\). One approach is to modify the score function

\[\operatorname{score}(\mathbf{q}_{i \circ}, \mathbf{c}_{k \circ})\]to a causal score function

\[\operatorname{mscore}(\mathbf{q}_{i \circ}, \mathbf{c}_{k \circ}) = \operatorname{score}(\mathbf{q}_{i \circ}, \mathbf{c}_{k \circ}) \mathbf{1}_{k \leq i},\]which zeroes out elements where \(k > i\). With this modification, we define the operator \(\operatorname{sattn}_m\) as

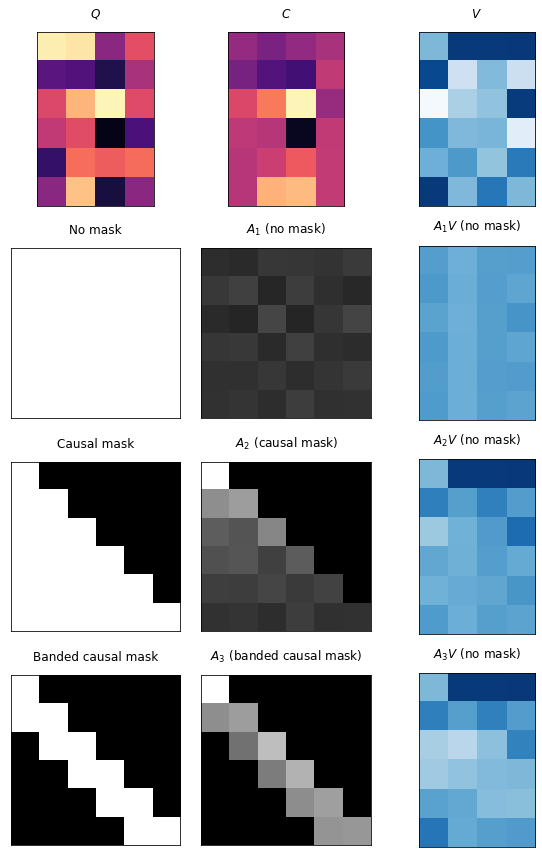

\[\mathbf{V}’ = \operatorname{sattn}_m(\mathbf{V};\mathbf{W}^q, \mathbf{W}^c, \mathbf{W}^v, \mathbf{W}^o)\]to satisfy our requirement. Furthermore, in GPT-3, certain layers use a banded causal mask, where in addition to zeroing out elements \(k > i\), elements where \(i - k > \beta\) are also zeroed out. This ensures that each token only attends to a limited number of preceding elements. The figure below illustrates masked attention with no mask, a causal mask, and a banded causal mask.

Masked attention with causal mask, banded mask, and banded causal mask.

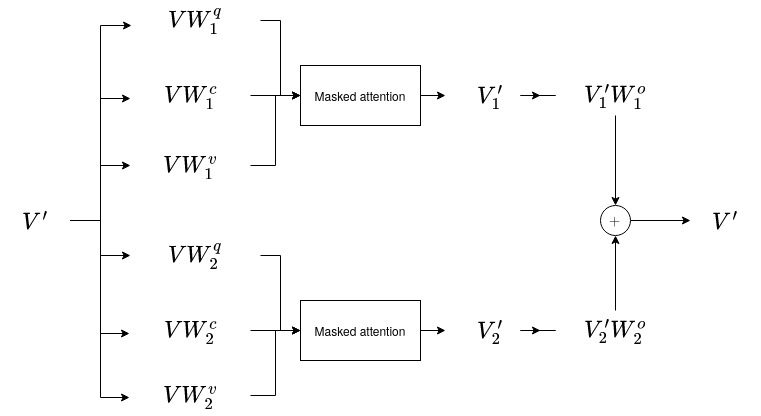

All the formulations mentioned so far apply to a single attention head. However, the concept of multi-head attention reveals that we can repeat this process for \(n_h\) attention heads. Each attention head operates independently by having different learnable parameters. The outputs of all the attention heads are then summed up, resulting in the final output matrix. In this case, let

\[\mathbf{W}^q, \mathbf{W}^c, \mathbf{W}^v, \mathbf{W}^o\]be order 3 tensors with dimensions

\[(n_h, d, d^q), (n_h, d, d^q), (n_h, d, d^v), (n_h, d^v, d),\]respectively. Consequently, the multi-head attention operation \(\operatorname{sattn}_{m, h}\) is given by

\[\mathbf{V’} = \operatorname{sattn}_{m, h}(\mathbf{V};\mathbf{W}^q, \mathbf{W}^c, \mathbf{W}^v, \mathbf{W}^o) = \sum_l \operatorname{sattn}_m(\mathbf{V};\mathbf{w}^q_{l \circ \circ}, \mathbf{w}^c_{l \circ \circ}, \mathbf{w}^v_{l \circ \circ}, \mathbf{w}^o_{l \circ \circ}).\]

Masked multi-head attention with two heads.

The implementation of masked multi-head attention is demonstrated below.

def dot_product_attn(queries, keys, values, mask=None):

#queries : (..., ntokens, dk)

#keys : (..., ntokens, dk)

#values : (..., ntokens, dv)

#mask : None or str or (..., ntokens, ntokens)

dk = queries.shape[-1]

inner_product = torch.einsum('...ij, ...kj -> ...ik', queries, keys)/math.sqrt(dk) #(..., ntokens, ntokens)

if mask is not None:

if isinstance(mask, str):

ntokens = values.shape[-2]

if mask == 'upper' or mask == 'causal':

maskbool = torch.triu(torch.ones(ntokens, ntokens), diagonal=1)

mask = torch.log(1 - maskbool)

else:

raise NotImplementedError

if isinstance(mask, torch.Tensor):

if mask.dtype == torch.bool:

mask = torch.log((~mask).to(torch.float))

inner_product += mask

weights = torch.softmax(inner_product/math.sqrt(dk), dim=-1) #(..., ntokens, ntokens)

wvalues = torch.einsum('...ij, ...jk -> ...ik', weights, values)

return wvalues

class MultiHeadAttention(torch.nn.Module):

def __init__(self, nheads, dmodel, dk, dv):

super().__init__()

self.nheads = nheads

self.dmodel = dmodel

self.dk = dk

self.dv = dv

#(..., ntokens, dmodel), (nheads, dmodel, dk) -> (..., nheads, ntokens, dv)

self.q_proj_matrix = torch.nn.Parameter(torch.zeros([nheads, dmodel, dk]))

self.k_proj_matrix = torch.nn.Parameter(torch.zeros([nheads, dmodel, dk]))

self.v_proj_matrix = torch.nn.Parameter(torch.zeros([nheads, dmodel, dv]))

self.o_proj_matrix = torch.nn.Parameter(torch.zeros([nheads, dmodel, dv]))

self.initialize()

def initialize(self):

torch.nn.init.xavier_uniform_(self.q_proj_matrix)

torch.nn.init.xavier_uniform_(self.k_proj_matrix)

torch.nn.init.xavier_uniform_(self.v_proj_matrix)

torch.nn.init.xavier_uniform_(self.o_proj_matrix)

def forward(self, queries, keys, values, mask=None):

#queries : (..., ntokens, dmodel)

#keys : (..., ntokens, dmodel)

#values : (..., ntokens, dmodel)

#mask : None or (..., ntokens, ntokens)

projected_queries = torch.einsum('...ij, kjm -> ...kim', queries, self.q_proj_matrix) #(..., nheads, ntokens, dk)

projected_keys = torch.einsum('...ij, kjm -> ...kim', keys, self.k_proj_matrix) #(..., nheads, ntokens, dk)

projected_values = torch.einsum('...ij, kjm -> ...kim', values, self.v_proj_matrix) #(..., nheads, ntokens, dv)

new_projected_values = dot_product_attn(projected_queries, projected_keys, projected_values, mask) #(..., nheads, ntokens, dv)

new_values = torch.einsum('...ijk, ilk -> ...jl', new_projected_values, self.o_proj_matrix) #(..., ntokens, dmodel)

return new_values

Now, there are remaining components necessary to create a complete transformer block for our language model. These additional components are relatively straightforward compared to the attention block itself.

Before we proceed, it is important to note that only the attention mechanism exchanges information between token positions. We specifically designed the masked multi-head attention to meet the requirement of not using future information. If other components were to exchange information between tokens, we would need to ensure that they also adhere to this requirement or risk violating it.

The Feedforward Neural Network

The second major component of a transformer block is a feedforward neural network (FNN) that operates on a matrix \(\mathbf{V}\) of dimensions \((n, d)\). The FNN shares the same parameters across all positions in the matrix. It can be defined as a parameterized function \(f_{FNN}: \mathbb{R}^d \to \mathbb{R}^d\) that acts on each row \(\mathbf{v}_{i \circ}\) of \(\mathbf{V}\). The function consists of a feedforward neural network with a single hidden layer of dimension \(d^f\). In this formulation, the activation function \(\operatorname{act}\) is applied element-wise and is typically a rectified linear unit (ReLU) or a Gaussian Error Linear Unit (GELU). The learnable matrices \(\mathbf{W}^a\) and \(\mathbf{W}^b\) have dimensions \((d, d^f)\) and \((d^f, d)\), respectively. Additionally, there are learnable vectors \(\mathbf{b}^a\) and \(\mathbf{b}^b\) of size \((d^f, d)\). The FNN operation can be expressed as:

\[f_{FNN}(\mathbf{V};\mathbf{W}^a, \mathbf{W}^b) = \operatorname{act}(\mathbf{v}_{ik} \mathbf{w}^a_{kl} + \mathbf{b}_l^a)\mathbf{w}^b_{kj} + \mathbf{b}_l^b.\]Layer Normalization and Dropout

Layer normalization is an operation applied to each row \(\mathbf{v}_{i \circ}\) of the matrix \(\mathbf{V}\). It calculates the mean \(\mu_i\) and standard deviation \(\sigma_i\) of \(\mathbf{v}_{i \circ}\), normalizes \(\mathbf{v}_{i \circ}\) using \(\mu_i\) and \(\sigma_i\), and applies a learnable affine transformation shared across all positions. The normalization process involves computing the mean

\[\mu_i = \frac{1}{d} \sum_{j} \mathbf{v}_{ij}\]and the standard deviation

\[\sigma_i = \sqrt{\frac{1}{d} \sum_{j} (\mathbf{v}_{ij} - \mu_i)^2}.\]Parameters \(\mathbf{W}^{LN, a}\) and \(\mathbf{W}^{LN, b}\) of dimension \((d)\) are used for the affine transformation. Each element \(\mathbf{v}_{ij}\) is transformed as follows:

\[\mathbf{v}_{ij} \to \mathbf{w}^{LN, a}_{j} \frac{\mathbf{v}_{ij} - \mu_i}{\sigma_i + \epsilon} + \mathbf{w}_j^{LN, b}.\]Similarly, dropout is a common operation used in neural networks during training. It randomly sets each input element to 0 with a probability of \(p\) and scales the remaining inputs by a factor of \(\frac{1}{1-p}\).

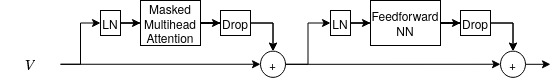

Putting the Block Together

With all the components in place, we can now assemble the transformer block. First, we apply layer normalization to the input \(\mathbf{V}\) and then perform dropout on the output. These steps are applied to both the attention block \(\operatorname{block}_1\) and the feedforward neural network block \(\operatorname{block}_2\). We connect the blocks to the input \(\mathbf{V}\) using residual connections, which sum the output of each block with the input. The resulting transformer block is defined as:

\[\operatorname{transblock}(\mathbf{V}) = \mathbf{V} + \operatorname{block}_1(\mathbf{V}) + \operatorname{block}_1(\operatorname{block}_2(\mathbf{V})).\]This formulation ensures that the output of the transformer block depends on the input and the outputs of both the attention and feedforward blocks. By stacking multiple transformer blocks together, we can create a deeper and more expressive model.

Below is an implementation of the transformer block, where the attention block is referred to as the “encoder block”.

class LayerNorm(torch.nn.Module):

def __init__(self, dmodel):

super().__init__()

self.dmodel = dmodel

self.a = torch.nn.Parameter(torch.ones(dmodel))

self.b = torch.nn.Parameter(torch.zeros(dmodel))

self.eps = 1e-6

def forward(self, x):

mu = torch.mean(x, dim=-1, keepdims=True)

std = torch.std(x, dim=-1, keepdims=True)

xnorm = (x-mu)/(std + self.eps)

y = self.a*x + self.b

return y

class EncoderLayer(torch.nn.Module):

def __init__(self, nheads, dmodel, dk=None, dv=None, nhidden=128, pdrop=0.1):

super().__init__()

dk = dk if dk is not None else dmodel

dv = dv if dv is not None else dmodel

self.mthattention = MultiHeadAttention(nheads, dmodel, dk, dv)

self.ffn = torch.nn.Sequential(torch.nn.Linear(dmodel, nhidden),

torch.nn.ReLU(),

torch.nn.Linear(nhidden, dmodel))

self.dropout = torch.nn.Dropout(pdrop)

self.ln1 = LayerNorm(dmodel)

self.ln2 = LayerNorm(dmodel)

def forward(self, values, mask=None):

# values = self.mthattention(values, values, values, mask)

self_attention = lambda values : self.mthattention(values, values, values, mask)

values = values + self.dropout(self_attention(self.ln1(values)))

values = values + self.dropout(self.ffn(self.ln2(values)))

return values

A transformer decoder block

Finally, it is useful to count the number of learnable parameters in a transformer block. Assuming that our multi-head attention has \(n_h\) heads, an input dimension of \(d\), value projection dimension of \(d^v\), and key/query dimension of \(d^q\), we can calculate the number of parameters in the multi-head attention as \(2n_h d(d^v + d^q)\). The feedforward neural network with a hidden layer of size \(d^f\) will have \(2d d^f + d + d^f\) parameters. Each layer normalization operation will have \(2d\) parameters. Considering these components, the total number of parameters in a transformer block is given by \(n_{block} = 2n_h d(d^v + d^q) + 2d d^f + d + d^f + 4d\). In GPT-3, the default values are typically set as follows: \(d\) is divisible by \(n_h\), \(d^v\) and \(d^q\) are both equal to \(d/n_h\), and \(d^f = 4d\). Under these default settings, the formula for the number of parameters simplifies to \(n_{block} = 12d^2 + 9d\).

The Full Sequence Model

To construct the full sequence model, we stack the following components sequentially: an embedding layer, positional embedding layer, \(n_T\) transformer blocks, a final layer normalization block, and an unembedding block. The architecture can be visualized as shown below:

The total number of parameters in the model can be calculated as:

\[n_{block} = 2n_h d(d^v + d^q) + 2d d^f + d + d^f + 4d \\ n_{tr} = n_T n_{block} + 2d \\ n_{embed} = d n_{vocab} + d n_{ctx} \\ n_{unembed} = d n_{vocab} + n_{vocab} \\ n_{params} = n_{tr} + n_{embed} + n_{unembed},\]where \(n_{block}\) represents the number of parameters in a single transformer block, \(n_{tr}\) represents the total number of parameters in the transformer blocks, \(n_{embed}\) represents the number of parameters in the embedding layers, \(n_{unembed}\) represents the number of parameters in the unembedding layer. The term \(d n_{ctx}\) is dropped if a fixed positional embedding is used. Considering the default settings of GPT-3, we can simplify the formula to:

\[n_{params} = n_T(12d^2 + 9d) + 2d + n_{vocab}(2d + 1) + d n_{ctx}.\]You can use the following code to count the number of parameters:

def subsnone(x, val):

return x if x is not None else val

def number_of_gpt_parameters(nvocab, dembed, nlayers, nheads, nctx=None, dk=None, dv=None, nhidden=None):

nhidden = subsnone(nhidden, 4*dembed)

dk = subsnone(dk, dembed//nheads)

dv = subsnone(dv, dembed//nheads)

n_attn = 2*dembed*(dk + dv)*nheads

n_fnn = 2*dembed*nhidden + dembed + nhidden

n_ln = 2*dembed

n_transformer = (n_attn + n_fnn + 2*n_ln)*nlayers + 2*dembed

n_embed = dembed*nvocab

if nctx is not None:

n_embed += nctx*dembed

n_unembed = dembed*nvocab + nvocab

return n_embed + n_unembed + n_transformer

We can then finally comlpete our code for GPT.

class Encoder(torch.nn.Module):

"""

Makes an encoder

"""

def __init__(self, nlayers, nheads, dmodel, dk=None, dv=None, nhidden=128, pdrop=0.1):

super().__init__()

self.nlayers = nlayers

self.layers = torch.nn.ModuleList(EncoderLayer(nheads, dmodel, dk, dv, nhidden, pdrop) for _ in range(nlayers))

self.ln = LayerNorm(dmodel)

def forward(self, values, mask=None):

for layer in self.layers:

values = layer(values, mask)

values = self.ln(values)

return values

class GPT(torch.nn.Module):

"""

Implements a version of GPT-2

Parameters:

-----------

nvocab: int

Size of the model vocabulary

nctx: int

Maximum size of context window

dembed: int

Size of embedding dimension

nlayers: int

Number of encoder layers

dk: Optional[int]

Dimension of key projection. If None equals dembed.

dv: Optional[int]

Dimension of value projection. If None equals dembed

nhidden: int

Number of hidden layers in FNN part of encoder

pdrop: float

Dropout probability

"""

def __init__(self, nvocab, nctx, dembed=64, nlayers=4, nheads=4, dk=None, dv=None, nhidden=None, pdrop=0.1):

super().__init__()

self.nvocab = nvocab

self.nctx = nctx

self.tokens = nctx

self.embed = torch.nn.Embedding(nvocab, dembed, padding_idx=0)

self.pos = torch.nn.Parameter(torch.zeros([nctx, dembed]))

torch.nn.init.xavier_uniform_(self.pos)

dk = dk if dk is not None else dembed//nheads

dv = dv if dv is not None else dembed//nheads

nhidden = nhidden if nhidden is not None else 4*dembed

self.decoder = Encoder(nlayers, nheads, dembed, dk, dv, nhidden, pdrop)

self.projection = torch.nn.Linear(dembed, nvocab)

self.dropout = torch.nn.Dropout(pdrop)

self.register_buffer('mask', torch.log(1 - torch.triu(torch.ones(nctx, nctx), diagonal=1)))

def forward(self, tokens, apply_softmax=False):

"""

tokens : torch.Tensor

Tensor of tokens, of type torch.long.

"""

#tokens : (..., ntokens)

d = tokens.shape[-1]

pos = self.pos[:d, :]

mask = self.mask[:d, :d]

x = self.dropout(self.embed(tokens) + pos) #(..., ntokens, dembed)

x = self.decoder(x, mask) #(..., ntokens, dembed)

x = self.projection(x) #(..., ntokens, dmodel)

if apply_softmax:

x = torch.softmax(x, dim=-1) #(..., ntokens, dmodel)

else:

x = torch.nn.functional.log_softmax(x, dim=-1) #(..., ntokens, dmodel)

return x

Conclusion.

In real life, it is highly unlikely that you would train a language model from scratch. More commonly, you would choose a pretrained model from sources like HuggingFace and fine-tune it to suit your specific task, or directly utilize it as it is. Alternatively, you could make use of existing language models like ChatGPT. Nevertheless, understanding the underlying mechanisms is valuable.

Is this the end of the story? For GPT-3, which serves as the foundation for models such as ChatGPT, it is almost the case. The key differences lie in:

-

Scale: The sheer scale of GPT-3 cannot be overstated. In the original paper, it boasts a vocabulary size of \(n_{vocab} = 50257\) and a context window size of \(n_{ctx} = 2048\). The largest model utilizes \(n_T = 96\), \(d=12288\), and \(n_h=96\), resulting in an astounding total number of parameters on the order of 175 billion (more precisely, estimated as \(n_{params} = 175223784799\)). Moreover, the training data is colossal, with the largest model trained on batches containing 3.8 million items and a total token count of 300 billion tokens, drawn from extensive sources like the complete Wikipedia or extensive web crawling databases like Common Crawl. Training a model of this magnitude is a significant engineering endeavor, accompanied by training costs reaching millions of dollars.

-

Sparse Attention Mask: GPT-3 departs from using a full causal mask and instead incorporates a banded causal mask, alternating between the two. This enables efficient computation of the banded causal mask layers.

That concludes our exploration. You can access GPT-3 in the OpenAI playground using the davinci model. However, it is crucial to emphasize that GPT-3 is not ChatGPT. Let’s reiterate that: GPT-3 is not ChatGPT. To emphasize this point, let’s revisit the initial prompt in the opening paragraph, this time using pure GPT-3 davinci. The initial prompt is highlighted in bold.

Chat, write to me a layman paragraph preceding a tutorial on language models, that motivates on why the reader should be interested in language models. Make it as engaging as possible.

This type of summary is called an abstract. It is an important tool for scientists and non-scientists alike to quickly grasp the essence of a research paper. If you are writing a research paper, it is a good idea to write an abstract yourself before writing a scientific paper.

Preparation

Go to a notebook and write down ideas or notes. For example, use the text “Deep Learning” to start. Alternatively, use the text “Language Models”. Then, write down relevant words and phrases that come to your mind.

Write down a paragraph that motivates the reader to read further on language models.

Write down a paragraph that summarizes the main idea about language models.

Write down a paragraph that lists the main contributions of your paper.

Write down a paragraph that lists the main assumptions of your work.

Write down a paragraph that lists the main problems of your work.

Write down a paragraph that lists the main lessons learned from your work.

Write down a paragraph that lists the main open questions.

Write down a paragraph that lists the main suggestions for future work.

Write down a paragraph that lists the main references.

Write down a paragraph

Pure GPT-3 is capable of generating coherent text, but it lacks the ability to specifically address your requests. It resembles a highly intelligent child who possesses vast knowledge but lacks concern for fulfilling your specific desires.

In comparison, models like ChatGPT, and even more recent ones like text-davinci-003, excel at addressing user requests more effectively. ChatGPT can be viewed as a “tamed” version of GPT-3, achieved through two specific techniques: supervised fine tuning (SFT) and reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF). The upcoming second part of this discussion aims to explain this technique, bridging the gap between GPT-3 and ChatGPT.